As you’ll know if you follow me literally anywhere on the internet, my debut novel The Glittering Edge is being publishing over the next week in the UK and the US!

Knowing my writing is about to be widely available to people who will love it and hate it and not give a shit about it brings up a hurricane of emotions. Excitement, fear, gratitude, dread, even apathy—it’s all there. How will TGE be received? Who will love it, and why? What could I have done better?

I’m probably not supposed to express doubts like that right now. I should be projecting confidence! Go buy my book because it’s worth spending the money!

For what it’s worth, I DO think it’s worth the money because I worked on it for like five years and I think it’s good lol (you can also get it for free from your local library! Support your library, always!). But these other questions that have run circles in my mind over the last few months—while inevitable—get at something deeper.

In this era of endless branding advice, post-til-you-drop, and being a relentless salesperson for our creative work, we begin to focus on the numbers as if they’re the end-all-be-all. If we get enough likes on a post, if we get a book tour or a certain number of sales, if we get enough attention, then we’ve done our jobs.

When you’re an author, this is really all you have to go on when you’re trying to figure out if you’re a success. You can’t measure the quiet moments, where someone is sitting with your book late into the night or reading it under their desk at school or during lunch or at the park. You can’t measure how people will feel about a book. How they’ll remember it.

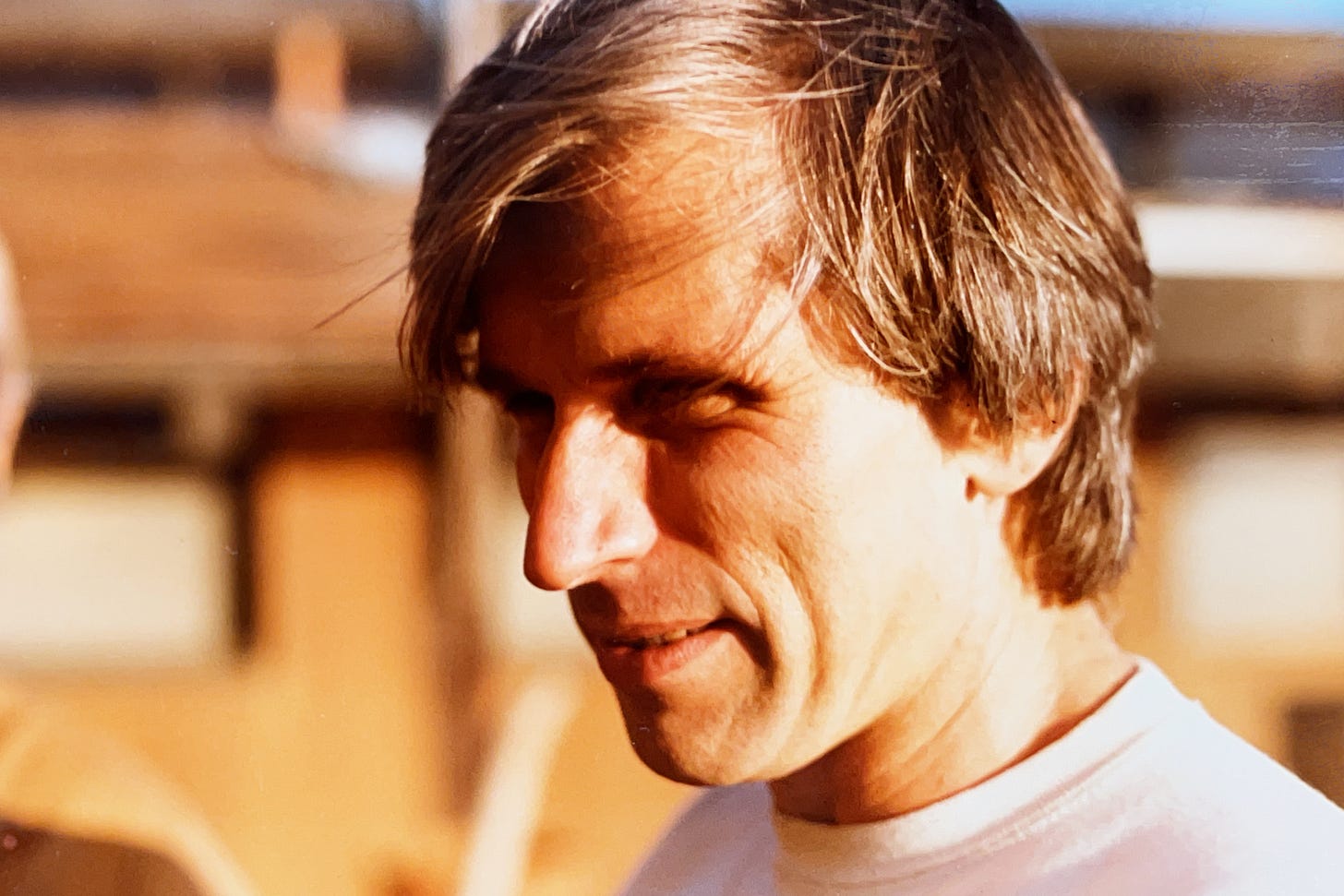

Which brings me to Uncle Dave.

I didn’t meet my uncle until I was six years old. He was my grandfather’s brother, and he came to visit the family when we were gathered in northern Michigan for a vacation on the lake (Huron). I didn’t know much about him except that he lived in California, a place I could hardly imagine.

I’ll always have fond memories of that weekend. It’s when Uncle Dave taught me to play chopsticks on the piano, which led to years of music lessons. It’s also when he told me, for the first time, that he’d worked as a writer for most of his life. As someone who already had a love for books and movies and TV, I couldn’t believe that I knew someone who’d written stories for a living. It made the dream feel that much more attainable.

It wasn’t until I moved to California years later that my uncle and I became close. By then he was in his seventies and I was in my early twenties. He had endless stories about living in LA during the 1970s and 1980s, hustling as a screenwriter while falling in and out of love and making friendships that lasted for the rest of his life.

Unsurprisingly, my questions focused on his writing. By that point in my life, I was writing like crazy, desperate to get agented and published. I knew that Uncle Dave had written for Hanna-Barbera, penning numerous scripts for shows like The Smurfs, Godzilla, and my personal favorite, Scooby-Doo. In talking with him about this experience, he shared that he’d never planned on writing for kids. He’d actually wanted to write dramatic films and literary plays—nothing a young child would’ve watched.

Since my whole family knew him for his work on children’s television, this was shocking. I wondered if I should stop asking about his time at Hanna-Barbera because maybe it brought up negative feelings. But Uncle Dave would talk about it on his own, without any prompting. Even though it was hard work, it was clear he’d enjoyed it. Writing for those shows hadn’t been his dream, but it had been a steady job. And he told me something that has stayed with me ever since:

“These shows reached kids all over the world. How could I ever be mad about that?”

When my uncle died in Fall 2023, I shared memories of him on social media. I talked about his love of long hikes and how the owner of his favorite restaurant at The Original Farmers Market on Third and Fairfax knew him by name (though the owner only referred to him as “James Bond” because of how handsome he was). I also talked about his writing.

After I shared these memories, I got so many messages from people who were amazed that he’d been involved in shows they’d grown up watching. His name isn’t widely known because it was often left off the credits (this has to do with the way Hanna-Barbera worked: people weren’t always credited if they were full-time employees at the studio), but these series were formative for so many people. For me and at least two other friends, Scooby-Doo and Godzilla inspired us to become working writers.

It wasn’t the legacy Uncle Dave chose, but it was the one he got. And, even if the other screenplays he sold were never made into films, he was happy to have had this career.

The reason I love reading and writing YA fiction is because these were the books that opened my world when I was a kid. I learned so much about friendship, relationships, and what makes a story gripping. These are the books that, to this day, have an impact on me and my writing. Multiple reviewers have said TGE reminds them of early aughts fantasy, and this is by design—in many ways, my debut is an ode to both my upbringing in small-town Indiana and the books that made me imagine a different future for myself. One in which I pay it forward by creating stories that provide comfort and a new way of seeing the world for the next generation.

But I can’t force anyone to read my books. I can’t control if or how I am remembered. Maybe TGE will be the book I’m known for; maybe it will be the next book I write, or the Webtoon I worked on from 2023 to 2024. All I can do is put some sort of truth on the page—truth in characters, truth in the form of rational magic systems, truth in the form of a fictional town that shares many characteristics with the places where I grew up—and hope someone else recognizes it.

While writers are often more introverted than other creatives due to the nature of our work, we still crave the same recognition. If people love our books, doesn’t that mean they love us? That they’ve accepted us?

Maybe we can’t help thinking this way. It’s probably human nature. Because writing, like other art, is about connecting. It is, at its core, begging someone to listen and to understand. It’s igniting smoke signals and waiting to see if anyone comes to your island. But connections are messy and unpredictable, and you can’t control anyone’s specific reaction. They might be angry because they loved the book and their favorite character got hurt, or maybe they’re passionate about it because of how much they hated every word on every page. In a way, both of these people are acknowledging us. We’re connecting with them.

The danger is when we start looking for nothing but praise. That’s when we as writers (and any other creatives) have to learn to let go.

Way back in 2014, I read an interview with Tavi Gevinson in The Great Discontent. She said, “I get surprised all the time by what people respond to in my work…My legacy is not in my control. It won’t matter to me and maybe not even to other people after I die, so what’s the point? I’m young, and there is a lot that I still want to create, so my first impulse is to shut up and get to work…”

The Glittering Edge is the first of what I hope will be many smoke signals. If you see it, won’t you come by?

Gorgeous from start to finish. So, so proud of you—and I know so many people will see truth in your work and love it deeply. <3

this was beautiful. so excited to read TGE 🤍 also omg tavi gevinson!